Why you still can’t buy a graphics cards according to a supply chain expert

- Why is the chip shortage happening?

“So here we’ve got demand, on the one hand, that’s just off the charts. And we’ve got the supply chain that is handicapped by virtue of getting access to materials, very constrained production capacity, and then slow transportation connecting the dots. You add it all up, and that’s where we are right now.” - Why is the chip shortage especially bad now?

“Even though supply chain risk management has been a common theme in business over the last, you know, eight to 10 years. They just didn’t prepare for what we call a Black Swan Event, which is what pandemic represents—something that we had not really witnessed on the scale that we’ve seen.” - What does this mean for AMD, Nvidia, and Intel?

“Where the PC industry finds itself is that they have highly dependent relationships with the chipmakers… They usually co-develop these chips together. And that’s a good thing and a bad thing. It’s a good thing because by working so closely together, you’re a very high priority when it comes to manufacturing. However, you are kind of wedged in, in that you’re dependent on that one, or a few.” - When will the chip shortage end?

“If we can just get our footing, meaning that demand tempers and we get away from this fever pitch for demand. And we do see supply capacities increase, transportation regain its footing, it could be maybe by summer of next year that we were not talking about this stuff quite so much.”

In order to buy a graphics card in 2024 you’ll need smarts, agility, and, most of all, a bit of luck on your side. Look at the bigger picture and the reason for this is simple: demand outstrips supply, leading to a semiconductor shortage. But what does it actually mean to not have enough chips? How did we end up in this situation? And how the heck does it get fixed?

In order to answer those questions, it’s important to look past the simple truths of empty shelves; that there’s not enough to go around. Instead looking as to why some of the largest companies in the world are unable to meet the tremendous demand of the moment. Because the silicon shortage is not only affecting sales of graphics cards and a specific CPU or two, but causing migraines at automobile manufacturers, logistics companies, service providers, retailers, and further afield.

Anyone sticking to the curve of cutting-edge technology is currently feeling the squeeze of the semiconductor shortage.

In hopes of explaining this phenomena, I’ve been speaking with Dr. Thomas Goldsby, the Haslam Chair of Logistics at the University of Tennessee’s Master’s of Science in Supply Chain Management online program, and a certified supply chain expert.

Bio

Professor Thomas Goldsby holds a BS in Business Administration, an MBA, and PhD in Marketing and Logistics. He was also the Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Business Logistics and former Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Transportation Journal. His research interests include logistics strategy, supply chain integration, and lean and agile supply chain strategies.

“I was taking part in an industry meeting a few days ago,” Dr. Goldsby says, “and a senior executive from a major company said ‘when things are going well in our supply chain we receive very little notice, we’re just kind of operating under the radar, and people don’t really call us out that much. But when things are not going well, when you can’t meet the basic business premise of delivering on your commitments to your customers, they’re gonna look to supply chain.'”

That’s largely true of PC gaming, too. When things are going well, we tend to ease up on the analysis of overarching industry trends and supply chain, distribution, or logistical concerns. We still care deeply about the manufacturing process of those parts that matter most to us, though the exact time and location of a stock drop at your local Best Buy tends to go by without passing remark.

But we’ve also had quite a few ups and downs in the hobby as of the past half decade—I’m talking more than your usual launch month jitters that see the shelves emptied for the hottest chips the moment they go on sale. With them we’ve grown more attuned to the prevailing headwinds of semiconductor manufacturing. No more so than the perhaps most deep-seated, unwavering, and ongoing silicon shortage, namely affecting the graphics card market, that has thus far continued through 2024 and into 2024.

There are multitude of reasons for this ongoing shortage. Ultimately, though, it comes down to factors affecting demand and those affecting supply.

“Let’s just start with the demand side of the equation,” Dr. Goldsby explains. “Certainly, the pandemic has driven up purchase and consumption experience of more and more electronic based products. As people shifted how they use their time, from being at work to being at home, and the toys, gadgets and technology required to keep your sanity, frankly, during the course of the pandemic drove intense demand.

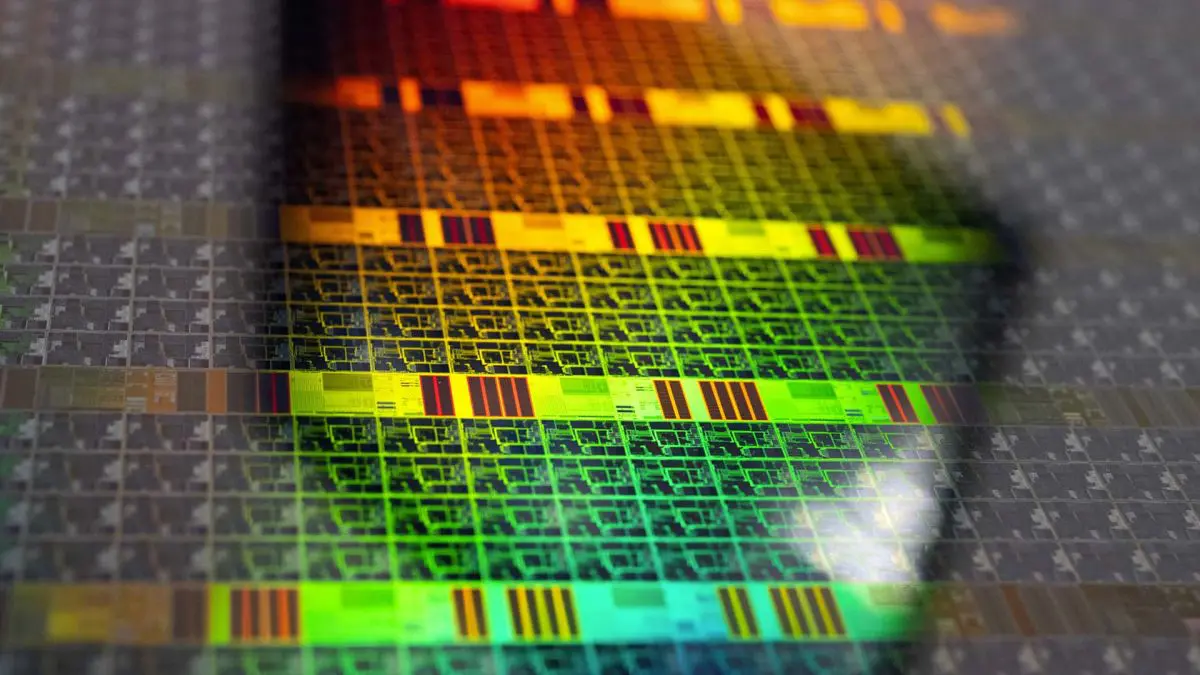

You can look at the silicon that goes into the wafer, you can look at the metals and minerals that go into the circuitry, to some extent, every single one of those inputs has been hamstrung in some way.

Dr. Thomas Goldsby

“However, that was preceded by a bit of a pause, where people didn’t quite know what to make of this pandemic.”

Such a pause preceding a significant shift in demand results in, as Dr. Goldsby describes, a V-shaped rebound, or drop-off and then rapid return, in demand. That in itself has wreaked havoc, but that’s hardly the end of it.

For graphics cards, demand constitutes gamers—those eyeing up the latest developments from both Nvidia and AMD—but also cryptocurrency miners riding the wave of buoyant market value, and companies looking to expand their online services with more capacity and capability.

“Getting to the supply side of the equation, you have to go back a little bit in history among the chip makers. We’ve really got TSMC, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp; you’ve got Intel; you’ve got Samsung; a few other smaller players. But you’re talking about a highly concentrated market of suppliers.”

TSMC is responsible for most of AMD’s CPU and GPU products, while Samsung is the manufacturer of Nvidia’s RTX 30-series. The go-to gut reaction is to decry these companies for not making more chips. And it’s true that would end the chip shortage, if it were so easy.

“That doesn’t happen overnight,” Dr. Goldsby tells me.

All of these companies have promised expansion and are in the process of delivering on those promises. Intel, for example, broke ground on two new factories in Arizona last month, for the purpose of expanding both Intel’s capability to meet chip demand and kickstart its new Intel Foundry Services project, which aims to go toe-to-toe with TSMC and Samsung in building chips for other people.

But even Intel and rivals TSMC expect shortages to continue until 2024, if not 2024.

And there’s more to this complex story than a handful of chipmakers. Because these major chipmakers have numerous suppliers, and these suppliers have suppliers, and so on and so fourth until you finally reach a company dealing exclusively in raw materials. It’s a complex chain, essentially.

“If you break down to the DNA level of what goes into a chip, and you can look at the silicon that goes into the wafer, you can look at the metals and minerals that go into the circuitry, to some extent, every single one of those inputs has been hamstrung in some way,” Dr. Goldsby explains.

“So here we’ve got demand, on the one hand, that’s just off the charts. And we’ve got the supply chain that is handicapped by virtue of getting access to materials, very constrained production capacity, and then slow transportation connecting the dots. You add it all up, and that’s where we are right now.”

Every bad thing happening at once

It would appear that everything bad that could’ve happened, in fact did. But as Dr. Goldsby rightly points out, “I’ve learned to never say never right? I mean, things could be worse.”

Okay, I won’t drop that nightmarish outcome on you without some light at the end of the tunnel. Dr. Goldsby does see the silicon shortage returning to normalcy in good time, but to understand how, it’s best to know what beast you’re dealing with.

“It has stretched the imagination, certainly, to find ourselves in this situation,” Dr. Goldsby continues. “And many people are blaming lean manufacturing systems.”

Just in Time manufacturing; often called a lean inventory system; or Toyota Production System, after the company that championed it during the mid-20th century; is a fairly simple concept, but one that’s grown in popularity with the manufacturing giants of the world. So much so that it’s the de facto way of doing things nowadays.

It all comes down to the idea of making “what is needed, when it is needed, and in the amount needed.” There’s little excess inventory at any given time, and as the market’s wants and needs fluctuation, so too does a company’s manufacturing capability.

It’s all a clever way of reducing what Toyota calls, in its native Japanese, ‘muda, mura, and muri’, which it takes to mean waste, inconsistencies, and unreasonable requirements on the production line. Similarly, and perhaps crucially to many, maintaining a slim inventory helps keep margins healthy and risk low, which aids, ultimately, in a healthy share price.

So last-minute-by-design manufacturing meets near-insurmountable global crisis and that leads to supply chain chaos. It’s easy to see the pattern, but as Goldsby explains, it’s not entirely the blame of a lean system of manufacturing. There are some systems of redundancy in place to prevent catastrophic slow down or collapse of the supply chain even if a company is abiding exactly to the pillars of Just in Time production—these systems simply weren’t cut out for everything going wrong all at once.

“The truth is, [lean production systems] are partially to blame. But those systems were always pretty able to handle the hiccups.”

“We might have seen a small surge in demand, we might have seen small delays in supply chain execution. And it could really kind of accommodate that. Hey, the ships are running behind, we’ll use air to ship product and we’ll get stuff overnight that way. Well, now, yeah, there’s not enough air capacity to do that.”

So we get to the unfortunate reality which is we’re feeling the impact of Covid-19 reverberating through the supply chain. And Covid-19 constitutes what Goldsby describes as a “Black Swan Event”.

“Even though supply chain risk management has been a common theme in business over the last, you know, eight to 10 years. They just didn’t prepare for what we call a Black Swan Event, which is what pandemic represents—something that we had not really witnessed on the scale that we’ve seen.”

AMD and Nvidia are contract manufacturing experts, and Intel runs the shop

As Dr. Goldsby points out, no company wants to be backed into a corner when it comes to manufacturing—it’s desirable to have options, even redundancy, in your supply chain. These things afford a company flexibility in times when things get tough. But unfettered opportunity to shop around doesn’t necessarily offer the means to produce the best processors, in fact it more than likely hinders those means, and that’s where things get interesting for PC gaming.

The likes of AMD, Nvidia extract top performance from their designs through tight partnerships with foundries, as Dr. Goldsby explains.

TSMC doesn’t want all the work, the blood, sweat, and tears that it put into these designs to just be handed over to a competitor.

Dr. Thomas Goldsby

“Where the PC industry finds itself is that they have highly dependent relationships with the chipmakers,” he says.

“They usually co-develop these chips together. And that’s a good thing and a bad thing. It’s a good thing because by working so closely together, you’re a very high priority when it comes to manufacturing. And you probably enjoy healthy margins on that business. And you’re willing to pay when push comes to shove, we’re going to face a shortage, and a manufacturer has to allocate a suddenly very finite supply. Where are we going to direct our limited time and resources? They’re probably going to direct it to where they have the most strategic relationships, long term interest.

“However, you are kind of wedged in, in that you’re dependent on that one, or a few.”

Think of the existing product lineup for a second: AMD’s Ryzen processors and TSMC’s 7nm process node, these two things are entwined. The same goes for the red team’s recent Radeon graphics cards. These were the gaming industry’s first 7nm products, and that fact played a large part in the marketing of these products.

AMD has benefited hugely from its work with TSMC to optimise and maximise its processors on the 7nm process node. That partnership runs deep, and a redundancy in supply, be that from a different manufacturer, supplier, or location on the globe, isn’t therefore easily navigated by it.

“TSMC doesn’t want all the work, the blood, sweat, and tears that it put into these designs to just be handed over to a competitor,” Dr. Goldsby says. “And so the arrangements are very tight, between the chipmakers, graphic cards makers, and then on to the PC and console makers. You tend to find very tight, highly controlled relationships between them, which doesn’t make it easy to find those alternatives and build that redundancy.”

But it means TSMC will make sure AMD does get capacity. So, in reality, a tight relationship between AMD and TSMC, or Nvidia and Samsung, or Intel operating its own fabs, has more than likely played a huge role in securing the supply these companies have enjoyed, and not been a detriment to it. That’s just not much of an olive branch during a tumultuous time such as this, when most semiconductor companies are in the same boat in terms of supply.

I also asked Dr. Goldsby if Intel is set to gain from its rare position of owning and operating its own fabs, something which only a few years ago seemed ill-advised.

“Well, to the extent that you own and control your own destiny, absolutely,” he explains.

“When President Biden holds up a wafer and says, ‘This is infrastructure’… You may see something of very dramatic coming out of the Biden administration saying we need to support this industry. And Intel is a US-based company, probably just pure speculation here, but it could benefit tremendously from the administration saying we need to subsidise it, we need to bolster this capacity.”

And Intel is more than a CPU maker, it’s opening its spotless clean rooms to other companies to build supply. No doubt that which plays into the company’s favour if outside investment comes knocking.

The Biden administration’s executive order outlines clearly the need for more robust supply chains: “Therefore, it is the policy of my Administration to strengthen the resilience of America’s supply chains,” the executive order states.

But it is just one example of a government spotting the need for robust supply chains following today’s ubiquitous supply issues.

And while us PC gamers are desperate for semiconductors, so are many other industries. Car manufacturers could have had it worse over the years, and may now only be leveraging their significant weight in the industry to start getting the chips they require.

“AMD can negotiate perfectly well with their suppliers. Sony can negotiate very well with AMD. These are, again, highly concentrated relationships. But the automakers are finally getting smarter and saying, hey, yeah, we’ve got substantial demand, we’re about 10% of the chip market right now, that’s going to be growing. And we need to leverage what influence we can have, and probably, you know, pay for it as well.”

So perhaps the wider world is waking up to the power of water-tight relationships with foundries. But should gamers fret about that? Probably not, because AMD, Nvidia, and plenty more gaming companies already knew that going in. They’ve been doing that for years, pioneering the fabless chipmaking model, and so they’re likely very well positioned to deal with the ongoing chip crisis as well as anyone might in these circumstances.

More supply: imperative or incidental?

“You’d like to just think, okay, just increase the capacity,” Dr. Goldsby says.

More capacity is on the way—a steady influx of absurd quantities of cash contributes to new process nodes, manufacturing facilities, and cutting-edge lithographic machines that can help expedite the manufacturing process. All of which helps a company get its chips into your PC.

Though there is a problem, the time it takes to implement new capabilities. Not only because that means there’s a baked-in delay to when a company can meet an influx of customer demand, but also because a company can never be too sure if that demand will be there once its new manufacturing facilities whir to life.

“As a chipmaker, you are running seven days a week, three shifts, 24/7 operations, you’re able to pre-sell everything that you make, you’re able to probably bolster price to unfathomable levels, you’re selling everything. That’s a pretty good situation to have, particularly if we’re talking about demand tempering itself.”

There’s no doubt that companies will want to maximise their profits and expand their total market, but the smart ones are probably not going to rush into meeting the sudden, perhaps unexpected, demand.

“We have something in the industry called the bullwhip effect, which is where a small change in consumer demand amplifies as you go upstream in the supply chain. And I think the chip makers, and even the folks that are supplying the chip makers, are going ‘hey, we’ve seen this game before, everybody’s crying for materials right now, crying for product, and as soon as we get that product online, where’s the demand?’ It’s kind of taking care of itself.”

This is what is known as phantom demand: demand that is present at one moment in time, usually due to over-ordering and shortages, but then dissipates once supply steadies. A good analogy is toilet paper during the first days of the pandemic: it was always clear there was plenty of toilet paper to go around, but sudden demand caused shortages and over-ordering. To begin making two times, three times more toilet paper to meet that demand only for shortages to end only a few weeks later would’ve been clumsy and risky.

Today @Intel CEO @PGelsinger marked the beginning of construction on two new chip factories, bringing Intel’s total investment in Arizona to more than $50 billion. https://t.co/VF9MY6gdQY pic.twitter.com/VRWzpGge4xSeptember 24, 2024

“So I think there’s extreme caution not to over build capacity,” Goldsby says.

The effect of overcapacity or overproduction can be dire, as even recent PC gaming history can attest to.

To dredge up bitter memories, during the cryptocurrency boom of 2017/2018 graphics cards were hard to come by. The shortages lasted quite some time, too, with demand for graphics cards for the purpose of cryptocurrency mining showing signs of sticking around for the long haul. So it looks like Nvidia, and to an extent AMD, leaned into this demand.

Until it went away. Suddenly. Cryptocurrency values dropped and demand for GPUs for mining went with them. This hurt both companies in the long run, but especially Nvidia as it had more to lose. The company’s share price dropped, which CEO Jensen Huang chalked up to a “crypto hangover” leaving it with excess inventory of graphics cards which in turn seemed to delay the subsequent release of the next generation of GPUs.

I bring this up with Dr. Goldsby and he mentions an apt comparison that bears repeating:

Tips and advice

How to buy a graphics card: tips on buying a graphics card in the barren silicon landscape that is 2024

“These chips, and graphic cards, are like fashion products, and they have short shelf lives and everybody’s looking for the newest and the greatest. So do you want to be sitting on a year’s supply of something that is at risk of becoming obsolete? You actually see that sometimes companies’ innovation cycles get slowed down because they’ve got to clear out this inventory.”

So is the answer ‘build more fabs’? Yes, but slowly and surely will be how any company will wish to proceed, and if that means things continue to be tight right now, well, so be it.

“It’s the time lag, the inability to match supply and demand in real time, and sometimes it takes weeks, sometimes months. In this case, we’re talking a function of years really to get those things in sync,” Goldsby explains. “So it’s very hard. When you have imbalances and customer expectations and the ability to serve those, they’re just not anywhere close to being in cahoots or consistent with each other.”

And if you’re making a huge amount of money selling everything product you make, what’s the rush?

Reviving old graphics cards might not be the answer anyone wants

So if the long-term solution to the chip shortage is time and patience, is there a short-term one? There just might be one, although so far we’ve only seen it implemented on rare occasions: bringing back old graphics cards.

It’s a contentious thought, I know, especially when that old GTX 1050 Ti on your local online retailer is selling beyond its MSRP many years past its prime. But there’s some critical thought to it: a graphics card is better than no graphics card. And recent rumours suggest Nvidia may go one step further by bringing back the RTX 2060, perhaps with a greater memory capacity, in order to partially supply the market.

I ask Dr. Goldsby for his thoughts on reviving old cards in this way.

“I would expect that to happen, particularly if it can be done in a nearer term than bringing new capacity on, it can be done much more economically. I think those decisions will be made, I wouldn’t be surprised if they happen among graphics card folks, chipmakers, as well as anyone out there, regardless of what they make. Even when we’re talking about automobiles, you know, an analogue speedometer; someone will probably buy it. We will be able to get that product out to market.”

But he touches on one important thing that could sway a company to reject such an idea, something I must admit hadn’t crossed my mind in quite this way.

“You always have to protect the brand, right? And you don’t want, particularly tech companies don’t want, to be associated with not being on the cutting edge, high tech, advancing the experience.

“And so they do have to be very savvy about going, ‘Hey, where can we make a buck? Where can we serve a need in the short term?’ In the long term, it is about the cutting edge technology. So you’ve got to be very careful not to diffuse that. You wouldn’t want one of those old technologies that end up in the hands of a PC Gamer reader, who’s very savvy and looking for a better experience, and then only to go, ‘this is terrible’.”

And this all comes back round to that apt comparison of tech companies as fashion houses. The latest graphics card is a designer item, and flooding the market with less than desirable options could be seen to weaken that. The way they innovate quickly, in Dr. Goldsby’s words, “that’s how they compete”, and these companies don’t spend millions of dollars marketing an image to throw that down the drain when supply becomes tight.

Now do I think that writes off any possible rerelease of the RTX 2060? No, because there are many ways to market that decision, or even try and not market that card at all, that may still make it worthwhile during these desperate times. But it does help make a point about the reaction to the chip shortage in general, and that is these companies will do a lot to protect their assets, brand, and, of course, share price.

So while we want to see quick action to get graphics cards in the hands of gamers, especially during uncertain times like these, it may be that we’re seeing companies take a more careful, risk-averse approach—perhaps even let the chips fall where they may.

So, when will the supply chain crisis end?

The question on everyone’s lips is when the supply chain crisis will end. Realistically there’s no firm answer but we have some rough pointers from those in the know: the likes of Intel, TSMC, and AMD. Those with access to the raw numbers.

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger offers realistic expectation as to when new capacity will come online to address some of the demand: “I think this is a couple of years until you are totally able to address it. It just takes a couple of years to build capacity.” And TSMC’s CEO, C. C. Wei, told investors back in April it expects shortages to continue into 2024, at least.

I do have confidence that that it will catch up.

Dr. Thomas Goldsby

Dr. Lisa Su, CEO of AMD, has also acknowledged that these are indeed strange times for chipmakers and supply.

“We’ve always gone through cycles of ups and downs, where demand has exceeded supply, or vice versa,” Dr. Su explained at the Code Conference. “This time, it’s different.”

“It might take, you know, 18 to 24 months to put on a new plant, and in some cases even longer than that. These investments were started perhaps a year ago,” Su continues.

There’s some consistency to their expectations, at least, and Dr. Goldsby firmly believes that there is an end in sight: “I do have confidence that that it will catch up, we will get more capacity online, it’s gonna take time and demand will temper a bit.”

“If we can just get our footing, meaning that demand tempers and we get away from this fever pitch for demand. And we do see supply capacities increase, transportation regain its footing, it could be maybe by summer of next year that we were not talking about this stuff quite so much.”

Indeed it’s not a rosy outlook, and no doubt PC gaming will have its fair share of ups and downs before there’s an abundance of graphics cards. But if we can only return to something close to normalcy in pricing, and demand eases a little, we can see the return of budget PC gaming—something we’ve lost all but totally lost all contact with today.